The Pains of KYC & AML Norms (#37)

Poor accountability, lack of outcomes, and high compliance costs underline KYC/AML

Welcome to the 37th issue of the Unit Economics. Today, I attempt to tackle the elephant in the room, KYC & AML norms, by highlighting the challenges that financial institutions - including payments companies - regularly deal with to comply with such regulations and where the regulators can help ease the pain. Dive in!

Know Your Customer (KYC) norms and Anti-Money Laundering (AML) measures are, quite frankly, a nuisance. They are complicated, onerous, and inconvenient to financial institutions and users alike.

But their existence is justified by the purpose they serve, that of combating financing of terrorism and of disallowing any party illegal access to the services of financial institutions, including for arms or drug dealing, human trafficking, and other illegal means.

On a global scale, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) is the body that sets the customer identification requirements for the 39 member nations under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2002 (PMLA). But on top of these requirements lie the additional mandates by the sectoral or local regulators such as the central banks and exchange boards. Combined, and as documented by the local bodies, the domestic standards for the KYC and AML norms are set up for the regulated entities (REs) to follow as part of their customer due diligence (CDD).

With this context, the rationale for forming KYC/AML norms can hardly be questioned. But the effectiveness of the norms, given their impact on the global financial system, is worth discussing. For start, today, the KYC mandates get saved from much scrutiny due to the (1) incapability of the larger audience to understand all the interactions that go behind establishing the identity of the customer or the business, and (2) our inability to measure the effectiveness of the norms with much of the information behind closed doors.

We do, fortunately, have a few proxies to understand the inefficiencies that arise due to KYC/AML frameworks. Before we dive into them, let me elaborate a little on what the standard KYC/AML process involves.

Basic Details: details that are often required to be self-declared by the customer during onboarding, including but not limited to name, gender, marital status, mobile number, and date of birth.

Government-Issued Identity and Address Proof: many countries follow the common method of accepting government-issued identity proofs to establish domestic addresses as evidence of customer identity. The mandates, usually, ask the customer to submit multiple such officially valid documents along with the photograph to match their identity (digitally or in-person) with that of the individual in the government-issued document.

Other Risk-related details: the regulated entities, especially banks, are mandated to also ask customers for other details including income, occupation, education, etc. apart from the identity check to put the customers into different risk buckets. Based on the risk profile of the user, the REs are pushed to perform an Enhanced Due Diligence for those above the risk threshold.

Suspicious Activity/Transaction Report: for REs, the regulatory framework on KYC/AML necessitates elaborate risk checks and maintenance of reports to track any suspicious activity. These reports are then periodically verified by the concerned regulators, and failure to comply with any of the norms can lead to high penalties.

All of this, although a little tedious, must seem reasonable on the first read. But the devil is always in the details. So, let’s go a level deeper. Where do things go wrong with the KYC/AML norms?

Financial Exclusion

The requirement to produce government-issued identity excludes many, most of whom do not have any ill purposes, from the formal financial system. For instance, the World Bank estimated that over a billion people on the planet do not have proof of identity, with the skew higher against the women and the poorest. This provides a good case that the KYC/AML norms, while providing security, are likely tools for increasing financial inequality. Think of it this way, those who have been away from the traditional financial institutions will continue to find it most challenging to access the digital finance economy (microloans, neobanks, payments applications, etc.) due to their lack of past records and access to identity documents.

High Compliance Costs

The costs of KYC/AML compliances run in billions globally with the additional responsibility on REs to (1) hire executives to manage and perform walk-in and video KYCs, (2) store large amounts of data, (3) monitor onboarded customers for KYC/AML checks (transactions and sanction screening), (4) perform periodic risk assessments and prepare SAR/STR reports, and (5) coordinate with multiple parties to build the systems that can handle all these processes. In an ideal world, these costs should be justified by the return (notional and actual) from keeping the policies in place. But the research by Ronald F. Pol suggests that the compliance costs of the AML policy run hundred times over (!) the funds that are recovered from criminal offences and questions whether the policy is the world’s most ineffective policy. Even if the accuracy of the numbers is doubted, the study does put the high costs and the limited impact in perspective.

Poor Accountability

The overall policy ineffectiveness of AML guidelines is often masked by the narratives of individual success stories. When the time comes for evaluating the guidelines, the poor results are instead blamed on the failure of regulated entities to properly implement the existing norms, even if there is sufficient counter-evidence to suggest that the issue lies with the poorly defined norms.

Ronald F. Pol goes in great depth in his paper to quote the lack of “outcome” based measures in the policy suggestions by FATF, which can be held responsible for the overarching focus of the governments on the processes rather than on outcomes or effectiveness. FATF, of course, shifts the ball in the regulator’s court to describe the poor outcomes.

The involvement of top regulators in building the regulatory frameworks further adds incentive to hide evidence of any policy failure and leads to minimal serious reviews of the core policy design features. Instead, the result is a perverse incentive to put hefty fines on regulated entities for any policy failures. These penalties, on a global scale, cost REs many billions – apart from the compliance costs as discussed earlier.

Worsens Onboarding Experience

This is likely the point that we relate the most to. We have all faced scenarios where we wondered why our marital status or occupation should be relevant for adding money to our payment wallets. The expansive lists of requirements for KYC during onboarding, despite the advancements in digital modes for asserting customer identity (video KYC, central government registry, etc.), continue to be confusing and inconvenient to the customers.

While the regulators attempt to balance the security concerns and the customer experience, the mandates leave little room for flexibility and instead push blanket guidelines and ad hoc amount caps for different types of use cases, lengthening the onboarding time and adding to the struggle for product managers and the customers in designing the onboarding. The processing time for Customer Due Diligence (CDD) continues to run in days for all customer types, forcing a waiting period for those that might have an immediate need for accessing the financial system.

Lack of Standardisation

EY finds that more than 40 different regulators in Asia-Pacific have varying approaches to KYC/AML mandates, unlike the consistent requirements that we see in the US/EU. The lack of uniformity in KYC/AML standards makes it challenging for REs to expand and adapt to the onboarding needs in different countries and lowers the speed of technological advancement by inhibiting collaboration between entities who must follow different rules in neighbouring countries.

Adverse Business Impact

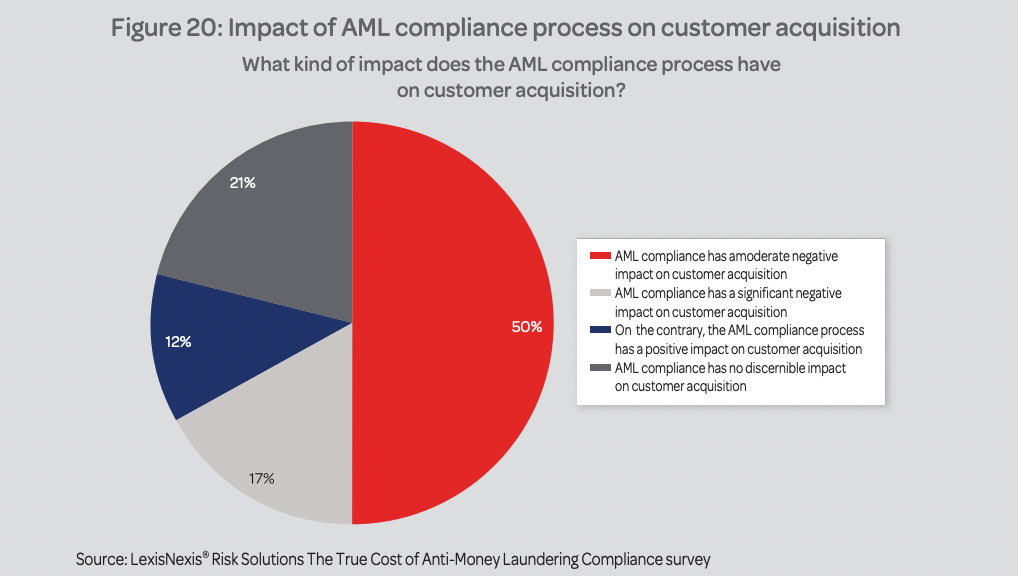

KYC/AML norms are a matter of serious fear for businesses that are responsible for implying policy effectiveness and incurring high costs of compliance. The direct compliance costs do not paint the whole picture, however. Based on the past surveys of businesses, we can see that the indirect costs of low productivity and poorer customer acquisition are equal negative externalities of such regulations.

While few quote the improved operational efficiencies due to procedural mandates, a high proportion of businesses look the other way and feel that the regulations either put a drag on their productivity, have a moderate negative effect, or threaten the business agility.

Similarly, an overwhelming number of businesses see a moderate or significant negative impact of the regulation on their customer acquisition. This is hardly surprising given the higher onboarding drop-offs that we see on KYC-related steps, lowering the onboarding activations and forcing businesses to spend higher on marketing and sales to match the level of acquisition that we would expect without the KYC.

Bottom line: in the world of Fintech startups with poor unit economics, KYC norms do not help.

Case in Point: Indian KYC Norms

There is evidence closer to the home of the inefficiencies drawn by these KYC/AML guidelines. If you have ever had to design an onboarding experience for a fintech in India, you have likely questioned the rationale for certain requirements – only to be told that the RBI or SEBI mandates it, so it must be followed. There is an insufficient rationale for fields on a case-by-case basis, however. And little continues to be challenged.

India, it must be noted, has progressed quickly through the IndiaStack on making the KYC process digital by introducing a central KYC registry to limit duplication of KYC efforts and by allowing Aadhar based authentication for identity. But the process is far from ideal still. In an extensive research by some members of the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), many such fallacies are highlighted. I will briefly cover the major points that paint an apt picture of the KYC issues that we face.

Rigid Address Proofs: Indian regulators go beyond the scope as defined by FATF and require customers to provide proof for multiple types of addresses: current, permanent, and residence. This directly excludes the migrant labor population from the formal system as such people would struggle to produce Officially Valid Documents (OVDs) such as utility bills, tax receipts to signal their ‘current’ address or even have a valid identity document to prove their permanent address. Further, updating the address in OVDs is time-consuming and complicated. In effect, the largely unnecessary addition of these one/two fields makes the onboarding compliance an impossible ask for the millions that are marginalized. The paper further compares India’s KYC/AML stance against that of the US and Germany’s, where there is greater flexibility in how the address is defined and capture. In the US, for example, FIs can verify the address details by conducting independent verification using public databases and credit reports, and through postal/telephonic means.

Inconsistent Technology Enhancements: Video and e-KYC are great additions to the KYC processes, but they struggle with details that are exclusionary in nature. First, the video KYC (unless self-assisted is allowed) is resource-intensive since an official from the RE must conduct it. This also introduces lag in onboarding. Second, those without the internet infrastructure continue to struggle to access any of the e-KYC or Video KYC routes with no facility for postal or telephonic KYC. Third, the inconsistency in who can and cannot do e-KYC muddles what constitutes a full-KYC for similar regulated entities. Lastly, the caps on amounts that can be loaned out on completion of KYC are restrictive and ad-hoc in nature. Such caps fall short of fulfilling the credit requirements of many that may be high creditworthy.

Enforcement Related Issues: compared to foreign jurisdictions, the Indian KYC framework does not provide sufficient remedial measures for businesses. There is limited scope to follow up with the regulator to seek clarification on rules or to review compliance prior to reviews. Moreover, sectoral regulators enforce strict penalties such as hefty fines, criminal sanctions, or cancellation of business license for the smallest of non-compliances. The fear of such penalties pushes many businesses to act in a highly risk-averse manner and to perform a level of due diligence that is more than required. Lastly, the entities regulated by the central bank have no avenue for appealing their sanctions, which makes the authorities seem almost draconian.

How can regulations then ease our KYC pain? The research paper goes on to suggest loosening the rigidity in address proofs, standard acceptance of e-KYC and Video KYC procedures for all regulated entities, and introduction of proper remedial measures and lower penalties for businesses that are in the throngs of sanctions. These are all practical suggestions that should be acted upon without great delay.

Final Few Words on the KYC Approach

The global KYC and AML measures have a problem of defining and measuring outcomes, and there is little accountability maintained by the regulators on the regulations. Given the high focus of Fintech innovation on customer experience, these norms are particularly troublesome.

With the problems of high compliance costs, financial exclusion – the onus should be on deriving policies that are flexible in establishing identity by allowing more proofs and channels as means to imply the same for the REs. Further, keeping in mind the high turnaround time for the onboarding, there is ample evidence to suggest that moving away from the staff-assisted methods of analog identity verification towards the more AI/ML-driven models as standard methods for verification would reduce the TAT and the compliance costs significantly.

More importantly, there is a need to develop a mandate to evaluate the effectiveness of the core design principles of the KYC norms and to make the results highly transparent to all the regulated entities involved. This should go a long way in establishing accountability and measuring the outcomes against the costs and adverse business impact that such regulations have.

These suggestions leave out certain considerations that regulators will point out but, if followed as per the more elaborate logic from the researchers, should be a good start to tackle the KYC ghosts.

What else can regulators do to make KYC and AML norms easier for businesses? Write back to me or add a comment below if you have any thoughts on the topic. In case you feel your friends or family would be interested in reading about payments, feel free to share the blog with them as well. See you in a couple of weeks!