Why are credit card balances falling? (#31)

Also: how the alternative credit payments, channels, and industry mix impact credit card usage

Welcome to the 31st issue of the Unit Economics. Today, I dive deep into the much discussed credit card balances data. Throughout the analysis, I try to ascertain the role of alternative credit methods, change in channel composition, and industry composition, among other factors in contributing to the fall in credit card balances.

P.S. You can still help fight COVID-led resource crunch in India by donating across verified organisations here.

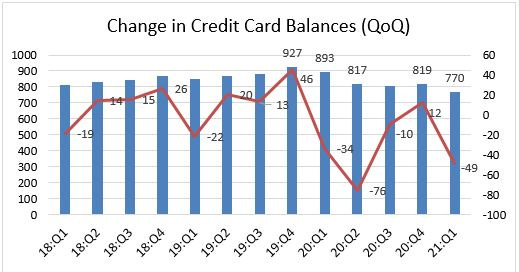

Last week, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York published the Household Debt and Credit Report for Q1 2021. The report and their press release stressed one data point: the $49Bn quarterly fall in credit card balances. This was the second biggest quarter-on-quarter fall in credit card balances since 1999. Definitely worth raising a few eyebrows. But then, when was the biggest fall? Was it during the global recession of 2008? Not really. The biggest quarterly fall in credit card balances, of $76Bn, was only three quarters ago. In Q2 2020.

Yet, the latest release attracted more eyeballs and headlines. Why would that be?

Two reasons justify the attention.

As opposed to three quarters ago, there are signs of recovery in retail consumption in the US, and even travel has resumed to a moderate extent – so, one would expect credit card usage to pick up as well, and

Secondly, with the world slowly transitioning towards the post-COVID phase, we perhaps seek more clarity on changes that are permanent versus those that are not today. And this Q1 2021 data point on credit card balances, in that long-term perspective, can have much larger implications.

Can the continuous fall in balances be an early sign of the consumer shift away from credit cards?

Can we assume this to be a reflection of the global credit card industry?

Are consumers moving towards alternate methods of payments?

Many such questions arise from the trend in credit card balances. Regardless of whether we can be certain of answers for all of them, the report gives us reasons enough to pause and reflect on the consumer behaviour towards credit card debt. In the rest of the sections, I try to answer some such questions by breaking down the data and combining perspectives from payments to make sense of why credit card balances are falling.

But to begin with: what are credit card balances?

In simple terms, it is the total amount of money that is owed to the credit card companies at the point in time. In this case, the snapshot of credit card balances is taken at the end of the quarter. Now, remember that this balance can be lower than the sum of our statement balances at the end of the month, assuming that some people pay off their due amounts early.

So, with this context, we can pause to think of the factors that would reduce the amount owed to credit card companies. Following a more top-down approach, we can start by breaking down balances into:

Number of existing credit card accounts, multiplied by

Average quarterly balance per credit card account

Where is the fall in credit card balances coming from?

We see that the drop in balances for the last quarter was ~$49Bn, but equally interesting is the more long-term drop from the Q4 2019 level – that of $157Bn ($927Bn to $770Bn).

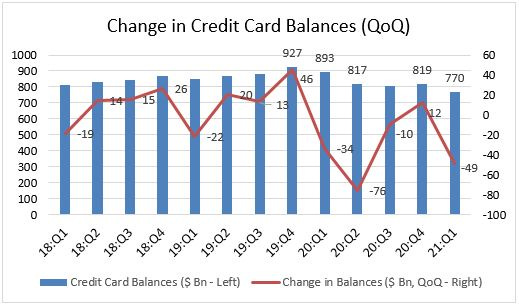

While the balances have dropped ~17% over the last five quarters, the change in the number of accounts from the Q4 2019 level is minimal at 2Mn or less than 0.5%. This tells us that people are not altogether abandoning their credit card accounts.

A caveat in the data is that joint accounts are not de-duplicated, i.e. a joint account for credit cards is counted twice. Since we are not doing exact calculations, we can assume the direction of the trend to be accurate regardless.

Now, since the change in the number of credit card accounts is negligible, i.e. not many people have closed their credit card accounts, we can hypothesize the drop to be coming from the average credit card balance per account.

And unsurprisingly, the fall in average quarterly account balance from $1,825 in Q4 2019 to $1,523 in Q1 2021 of ~16% corroborates our hypothesis.

Now, what can lead to lower average account balances?

This is similar to the question we started with, but we have cancelled one of the potential reasons. We know, for instance, that people are not completely disregarding their credit card accounts but are instead lowering their usage or utility of it. On a broad level then, we can further break down the fall in balances into two factors:

Lower spend through credit cards, or consumption if you may, which directly lowers the upper limit of the credit card balances that can get accumulated

Higher paydowns among credit card holders, which could be in the form of early payments and lower delinquencies. This is driven by either improved ability to pay credit card debt quicker or by a lower appetite for debt.

We have reasons to believe that the fall in balances is due to a combination of both metrics. But which factor is more at play here?

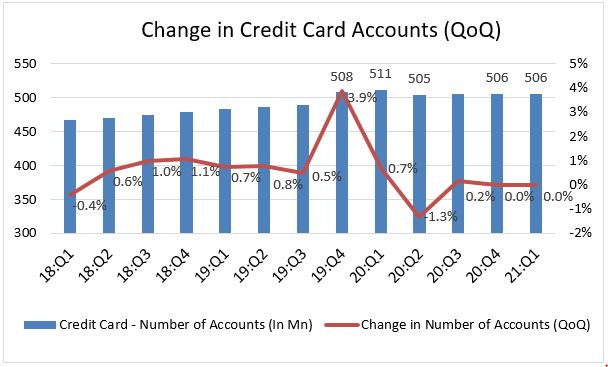

We start with the paydowns first. Are we seeing an unusually low proportion of delinquencies?

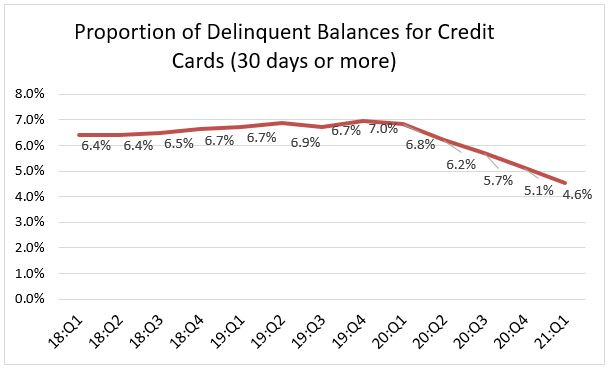

We can see a gradual drop from the last five quarters in the 30 day+ revolving balances. But, let’s do some napkin maths to see if this is the main driver of lower balances.

The overall credit card balance in Q4 2019 was $927Bn, which reduced to $770Bn in Q1 2021 – a drop of $157Bn

We see in the graph above that ~7% of the overall balances were newly delinquent during Q4 2019, while the delinquent balance for Q1 2021 was only ~4.6%. We can assume that the difference in the absolute value of delinquent balances for the two quarters should roughly be the contribution of early paydowns to the overall fall in credit card balances.

This would amount to ((927 x 7%) – (770 x 4.6%)) = ~$30Bn or 19% (30/157) of the overall fall in balances.

The 19% is a significant figure. However, it does not give us the complete contribution of early paydowns to the overall credit card balance fall. We do not have the numbers for balances that are due by 0-30 days, for instance. But, from the American Banker’s Association’s credit card market monitor, we can make out two interesting points:

The number of dormant credit card accounts increased 1.2 percentage points during 2020.

The number of revolving accounts fell by 4.4 percentage points to 39.7% during 2020.

Both of these factors feed into lower credit card balances per open account. This is bad news for credit card issuers, but great for the consumers, who seem to be turning more responsible – even if only during the pandemic.

Unfortunately, we do not have the numbers for Q1 2021 in the ABA report. But, for reference, even if we were to assume that the contribution to credit card balance of an average dormant or revolving account to be similar to the median – the drop in overall balances due to dormancy or low revolving accounts amount to less than 6% of the overall balance for the period. Thus, explaining less than 50% of the drop.

We can, perhaps a little imperfectly, assume then that the drop in balances is primarily on account of lower credit card spend to begin with. Our problem statement changes slightly once again.

Why are people spending less through credit cards?

Since we have devoted ourselves to a top-down approach where we break down one variable at a time, we can do the same for low credit card spending, which is a function of the following:

Lower willingness to spend using credit cards: the willingness can go down due to the availability of better payment alternatives or due to averseness to credit cards. The latter part can be linked to the poor value proposition of the cards or other significant macro factors.

Lower ability to spend using credit cards: the drop in ability, instead, would be a function of a drop in credit limits, stricter underwriting, or of change in conditions that limit expenditure for certain channels or industries.

We can start with the factors that could have possibly lowered the willingness of credit cardholders to use credit cards.

Has the willingness to spend using credit cards gone down?

A. Better Payment Alternatives

Better credit alternatives, and specifically Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL), have been touted as one of the main reasons behind the fall in credit card balances. We know that BNPL, at a high-level, is a direct payment substitute to credit cards, although it is not exactly treated as a form of debt today.

However, multiple arguments counter the claim that BNPL is driving the credit card balances down, with two of them recently highlighted by the Bank of New York’s Research and Statistics Group.

We see in the graph above that there is a larger drop in balances from consumers that live in the higher-income zip code areas. This goes against the straw man we would have made if BNPL or other alternative credit payments were to be the driving factor.

Moreover, the growth in BNPL is largely dependent on its usage by Gen-Z and the millennials, i.e. by 18-40 year olds. However, the graph above throws revealing insights by highlighting that it is the older borrowers that show the biggest drop in card balances. And instead, the 20-29 year old cardholders are carrying credit card balances that are close to the pre-pandemic levels.

If the above two statistics do not somehow counter the BNPL-argument for you, remember that BNPL volumes for 2020 were estimated to be around $89Bn, which is less than 10% of the overall credit card volumes. Moreover, even in the best-case scenario, if we assume that BNPL spends in Q1 2021 were half the overall 2020 spends, of which 25% - optimistically – displaced what would have been credit card spend. Then, we would end up with (89 x 0.5 x 0.25 =) ~$11Bn of credit card balance that was taken over by credit cards. A figure that is less than 25% of the overall fall in balances for the quarter.

So, if not BNPL, are debit cards taking over the credit card spend?

This question perhaps justifies an article on its own, given how often it has been asked over the last year. The growth in debit cards and the consequent pull-back in credit cards might seem directly correlated. However, we must remember that a good part of the displacement is coming from lower cash usage. And in doing so, we might want to keep the rationale for the fall in credit card usage separate from debit, as the value proposition of the two products is widely different – although both are forms of payments. This is a common phenomenon across countries today, even in Germany – where cash still dominates.

Take the words of Visa’s CEO, Alfred Kelly, in the earnings call for instance: “Debit has become the cash of the e-commerce world”. He noted in the call that the expected continued shift away from cash is likely to benefit both debit and e-commerce transactions, but not necessarily at the cost of credit. For example, Visa saw growth in credit transactions in Q1 2021 YoY and Mastercard, with larger dependency on credit, also expects credit spend to return to normal levels soon.

B. If not credit card alternatives, could it be other macro factors?

We cannot estimate the exact impact of forbearance programs or government stimulus checks on credit cards in the U.S., but the fiscal support is likely to have had a big influence on the liquid incomes of individuals, and perhaps even contributed to lower delinquencies on credit cards. Moreover, with consumer confidence up as visible from higher quarterly retail sales, we can say for certain that willingness to spend has improved and should translate to credit cards as well – especially with banks lowering their underwriting standards.

Summary: The push from banks and the value proposition of credit cards through rewards should keep the willingness for credit card usage high once the impact of fiscal support wears off. Moreover, with the fall in credit card balances coming mostly from the wealthier and older generation – the degree of impact of alternative forms of credit or debit cards seems exaggerated. Importantly, for the older and wealthier generation, a credit card is likely not viewed as a form of debt, as much as it is viewed as a status symbol or a way to earn reward points/miles and delay payments that they are perfectly capable of making even without the facility of debt.

To sum up, as the economy opens up with higher vaccination, the older generation can be expected to raise their willingness to spend through credit cards.

Has the ability to spend using credit cards gone down?

A. Lower credit limits or stricter underwriting

If you have been following the payments space, you have likely come across headlines of banks increasing marketing expenses or lowering their underwriting standards to push credit card usage. Both are tough to quantify, but we can be sure that stricter underwriting is hardly a worry for the consumers.

But have the credit limits for existing users lowered? One data point can answer that.

We see that, of the credit card limit available, only 20.1% was being utilized by credit card holders, and this proportion had been falling from Q4 2019, when it was 23.8%. This neatly tells us, one, that the credit limits have not relatively lowered for the credit card customers. And, two, that the cardholders have been gradually lowering their usage of the cards – relating strongly with our earlier premise. Given this data point, credit card limits should have hardly been a hurdle in the last year.

B. Limitations to Spend on Certain Channels or in Industries

Lastly, we look at whether the ability to spend through credit cards was somehow restricted on certain channels or in industries.

We know that share of e-commerce has gone up tremendously due to COVID, but what do we know of its impact on credit cards?

We know that distribution for payment providers is easier online, and there is today higher competition to get your method of payment top-of-mind for the customer online than it is at point-of-sale/offline.

If we look at the data above, we can make out that credit cards are an important method of payment for both online and offline transactions in the U.S.A. Moreover, we can also see that the share of credit card spend is higher for offline transactions than it is for online. Now, given that the purchases of many different kinds of offline goods such as grocery have turned into online purchases, we should expect the share of credit card purchases for goods & services to fall, especially with competition from digital/mobile wallets.

Therefore, the shift from offline to online purchases for many traditional industry goods & services can be a major contributor to the fall in credit card spend. Again, the basic napkin maths can give us the extent of the impact.

Assume that the distribution of offline to online purchases was 70:30 in Q4 2019, but has since become 30:70 due to COVID restrictions.

If we assume that the proportion of credit card spending was 38% and 30% respectively across two channels all this while, then the share of credit card volumes would be a simple weighted average.

Q4 2019: (70 x 38%) + (30 x 30%) = 35.6%. The same share in Q1 2021 would be (30 x 38%) + (70 x 30%) = 32.4%. This should give us a fall in share of overall credit card transactions of 3.2% on absolute basis or ~10% (3.2/35.6) of overall credit card volumes due to change in composition of channels.

However, this does not account for the displacement of cash that would help credit cards or the marketing/promotional expenses. A fairer estimate here then would be for the change in channel composition for payments to account for ~5% of the drop in balances for credit cards. However, with the economy slowly opening up and retail sales growing, this should have likely not been the biggest factor limiting credit card usage in Q1 2021.

So, can it be the limitations for credit card usage in certain industries?

It is an open secret in the payments industry that the lack of domestic and international travel has weighed heavily on credit cards during the past year, especially with credit cards centring their value proposition around rewards for travel, and expenses on fuel, movie tickets among other Travel & Entertainment (T&E) categories.

But to what extent have T&E restrictions impacted credit card usage?

A good reference to understand this would be the Q1 2021 earnings presentation of American Express, a company that powers more than 10% of all credit card transactions in the U.S. and that relies solely on credit cards.

For context, American Express divides its billed earnings into two segments: Goods & Services (G&S), and Travel & Entertainment (T&E)

We see in the table above that although G&S revenues have grown YoY for the quarter, T&E continues to be down by 50-60%. With a 14% proportion of the portfolio, the lag in T&E is sufficient to bring down credit card billed revenues by 9% YoY. If we were to take this at the face value, this would most clearly explain the low credit card balances – more so given that the fall in balances is higher for the older and wealthier consumers, who likely spend higher on T&E categories.

Another interesting point that corroborates our earlier finding in the earnings presentation is the the online (23%) versus offline (-9%) YoY growth of the G&S segment for American Express. It shows that the share of offline spend remains low YoY for credit, which likely impacts credit card’s share of overall spend.

Summary: It seems that more than willingness, it is the ability to use credit cards that better explains the fall in credit card balances. While the underwriting standards or credit limits are hardly any issues, the change in channel composition from POS/offline to the online and slow resurgence in T&E categories likely account for lower balances for the wealthier and older generation.

Final Few Words

The deep dive was meant to understand why credit card balances continue to fall and unlock behavioural insights on credit cards along the way. We find that the lower spend in T&E categories, changes in channel composition for payments, and fiscal stimulus seem to be contributing to a lower willingness and ability to use credit cards. However, with the travel expected to return within the next year as vaccination efforts ramp up, and with fiscal stimulus likely to not continue – we can expect a high proportion of credit card spend to be back to pre-pandemic levels within 2-3 quarters. Lastly, given that e-commerce is likely to retain a high share of overall spending, we can see a small proportion of credit card spend move towards the newer method of payments, although that can potentially be negated by cash displacement.

Either way, rumours of the credit card’s death are greatly exaggerated.

If you have any views or feedback to share, feel free to add a response below or to share your thoughts with me over Linkedin. In case you feel your friends or family would be interested in reading about fintech or economics, feel free to share the blog with them as well. See you in a week or two!

Very interesting article! Do you have similar insights for India?